How Adults are Rediscovering Christianity Through Baptism: CBS Reports

CBS Mornings recently reported that since the COVID-19 pandemic, a large number of adults — particularly Gen Z men — have been baptized into the Christian faith.

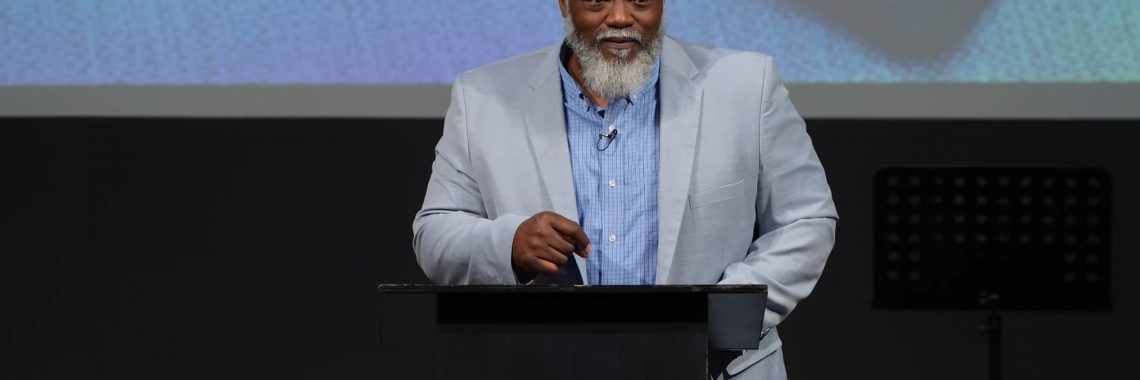

During its news segment, CBS highlighted a massive baptism service recently held on the California coast.

We have shared before about the “quiet revival” taking place in America and the U.K.

Bible sales in America skyrocketed in 2024, and this year the American Bible Society released its annual “State of the Bible” report that examines Bible use and scripture engagement. The report found, “Millennials are leading the way in this move toward greater Bible Use, and in every generation men are using the Bible more.” The report also found a little more than one in three Gen Z adults (36%) qualify as Bible Users.

While pollsters have reported for years about the decline of weekly church attendance, Gallup announced in June that a growing share of Americans actually see religion’s influence increasing.

It’s good to see more Americans coming to faith in Jesus and engaging with scripture. As President Reagan said during a speech in 1984:

The truth is, politics and morality are inseparable. And as morality’s foundation is religion, religion and politics are necessarily related. We need religion as a guide. We need it because we are imperfect, and our government needs the church, because only those humble enough to admit they’re sinners can bring to democracy the tolerance it requires in order to survive. . . .

Without God, there is no virtue, because there’s no prompting of the conscience. Without God, we’re mired in the material, that flat world that tells us only what the senses perceive. Without God, there is a coarsening of the society. And without God, democracy will not and cannot long endure. If we ever forget that we’re one nation under God, then we will be a nation gone under.

Hopefully this “quiet revival” is one that will continue to spread.

Articles appearing on this website are written with the aid of Family Council’s researchers and writers.